Visualizing the Range of Glaciers

This page served as a landing spot for sharing bits of my undergraduate environmental science honors thesis and related printmaking work. The North Cascades in Washington, the place I know as home, hold many glaciers that have complex ties to both ecological and human communities. Climate change is rewriting the state of these glaciers and the relationships that they can sustain. Although these connections are usually described by science, art is an expansive form of communicating a shifting landscape and its inhabitants. My project strove to explore a remarkable place in flux with various ways of knowing - scientific, personal, artistic, anecdotal. Enjoy these snippets, or download my entire thesis “Visualizing the Range of Glaciers: Science, Art and Narrative if you care to.

Scroll II

Relief and intaglio prints, collaged

Rives BFK, sekishu, and washi paper

22 x 80’’

Background on the elements of Scroll II.

Reading from the bottom up, or the top down, or from the middle out, this scroll tells several stories. Many small prints accumulate here as a testament to complex, beautiful moments on Easton Glacier and Mt. Baker from the summer of 2020. Scroll II is the first of three scrolls to be completed. Each focuses on a different time period and set of narratives.

Raven surveys the watershed from the high reaches of the volcano. The Deming Icefall splinters below.

Each of the five animals in this print are made up of shapes that were inspired by the patterns of snow melting off of the glacier’s blue ice. Although they rise from a common source, each animal has their own character and story.

Two scientists “go fishing”. They lower a weighted and metered rope into a deep crevasse on the Easton Glacier.

By collecting data on snow depth, the team can calculate the mass balance of the glacier. In a good year, thick snow insulates the glacier from melt and there isn’t much bare ice to be seen. The rope sinks 3, 4, 5, meters down into the snow-topped crevasse before reaching the glacier ice. To stay healthy, the glacier needs to retain snow over 65-70% of its area. Unfortunately, there are a lot of bad years when snow vanishes from much more of the glacier.

During their annual field work, the team also keep tabs on other glacier responses to climate change, such as streamflow, crevasse depth, and the location of the glacier terminus.

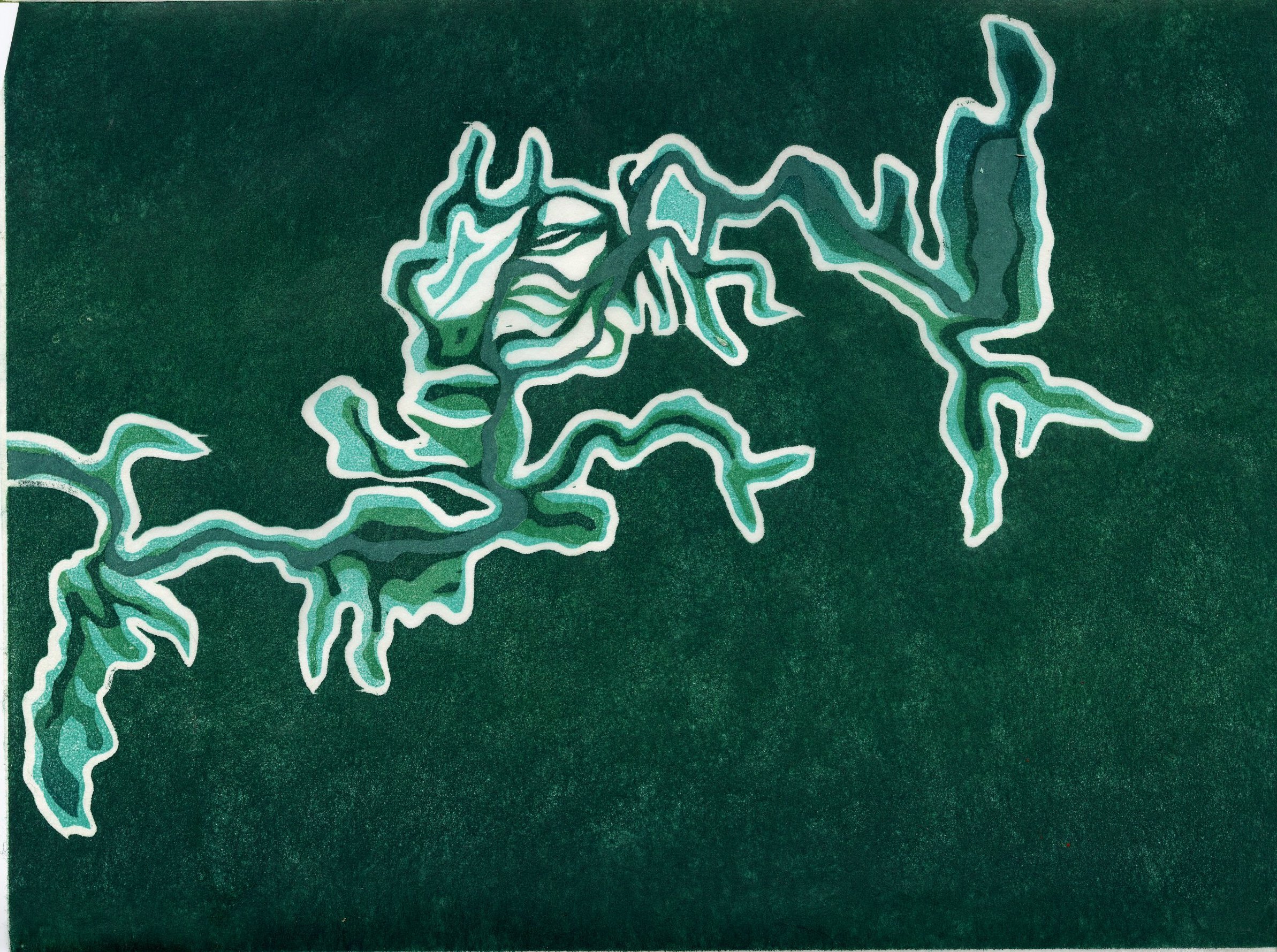

This tricolored puzzle has the texture of a frothing glacial creek. But the shapes show something much more macro: watersheds. These are the three forks of the Nooksack River.

The three forks drain the area west and south of Mt. Baker. Of the forks, the North is fed by many glaciers, the Middle by a few, and the South no longer receives any glacial melt. Anadromous fish, including the five species of Pacific salmon, thrive in habitat created and maintained by glaciers and glacial melt. Will the salmon of the South Fork of the Nooksack soon be ghosts? And what will happen when a piece of the puzzle goes missing? Fortunately, dam removals and stream restoration (including planting hundreds of trees and engineering dozens of new log jams) are giving the fish places to go in a warming world.

The stream rips downhill, across vacant moraines, through meadows and into the lush forest.

The cold water carries nutrients and organic carbon that sustain ecosystems. It can be rich in glacial flour, the fine sediment that diffracts light in such a way that lakes and streams appear milky green or brown. I envision the stream and its sediment nourishing trees, fish, marmots and flowers on its journey to the sea.

Meadow, Pika, Ellipsis.

The active pika collects mouthfuls of alpine grasses and flowers. She doesn’t hibernate, so she survives off of foraged haypiles throughout the winter. Pika live in talus fields, using rocks as a pantry and a shelter. They temperature sensitive, and can die when exposed to much more than 70° F. This animal considers her next move: Move up into the empty moraine? Will there be flowers?

Organizations and Research Teams:

North Cascades Glacier Climate Project

Long-term monitoring program for North Cascades glaciers

Nooksack Tribe Natural & Cultural Resources Department

Stewarding cultural, water and fisheries resources in the Nooksack

Nooksack Salmon Enhancement Association

Working hard to improve salmon habitat in the Nooksack watershed

View from the studio, printing one block one hundred ways…

I proofed each of my blocks in different colors, on different papers, and in different layers to build up a library of pieces that I could assemble for Scroll II and the accompanying test scrolls. For this project I used around 20 blocks/plates made of wood, copper and acrylic.

Photo by Sarah Morgan

Easton Doodles

These are various iterations of my Easton Glacier woodblocks. The two layers of images 2, 5 and 6 started out as sketches, which I manipulated in Illustrator and Photoshop, then laser cut into plywood. From there, I printed woodcuts the traditional way, with ink and a press. Finally, scanned those prints and relayered and colored the scans digitally.

Prints 1 and 2 are inspired by the colors of wildfire smoke.

Prints 3 and 4 are experiments with color, fresh off the printing press.

Prints 5 and 6 are just for kicks.

Sholes Imprints

Facing Mt Baker and the upper part of the Sholes Glacier (terminus below to the right). Can you see the forms of creatures emerging with the bare ice?

The Sholes Glacier flows down the north east side of Kulshan/Mt. Baker in Washington State. It feeds the North Fork of the Nooksack River, the short icy artery that connects Bellingham Bay to Kulshan, the 10,781 foot tall volcano. The Nooksack tribe calls this land home. So do many furry, scaly and feathered brothers and sisters.

Spend any time near the mountain and the lives of animals will quickly chirp, swoop, slap and wriggle their way into your awareness. This summer I spent a night on the Nooksack River, and I could feel the silver splash of salmon and the gaze of an eagle all evening. Later, we hiked Ptarmigan Ridge and counted nearly 50 mountain goats. The gray flash and squeak of pika is a frequent companion alongside the trail. These animals are emblems of the North Cascades. They are also endangered, each impacted by retreating glaciers and changing climate in different ways. With these imprints inspired by the Sholes Glacier, I show the beauty of their symbolic bodies and experiment with how we feel in their absence.

Back in July, I had a conversation with Jezra Beaulieu, who works as a water resources specialist for the Nooksack tribe. We discussed the research that she and Oliver Grah do, the connections between glaciers and salmon habitat, and how the Nooksack tribe is planning for climate change. In the portion of our conversation where I asked (as I always do) what forms of communication she found particularly effective at imparting data related to ongoing environmental change and adaptation, she mentioned the Nooksack Vulnerability Assessment.

“The climate of the Nooksack River watershed is changing, and is projected to continue to change throughout the 21st century. In addition to rising temperatures and exaggerated patterns of seasonal precipitation, the watershed is likely to experience greater wildfire risk, more severe winter flooding, rising sea levels, and increasing ocean acidification. These changes will have profound impacts on the watershed’s plants, animals, and ecosystems, including changes in species distributions, abundances, and productivity; shifts in the timing of life cycle events such as flowering, breeding, and migration; and changes in the distribution and composition of ecological communities. Understanding which species and habitats are expected to be vulnerable to climate change, and why, is a critical first step toward identifying strategies and actions for maintaining priority species and habitats in the face of change.”

Morgan, H., and M. Krosby. 2017. Nooksack Indian Tribe Natural Resources Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment. Climate Impacts Group, University of Washington.

The Nooksack Vulnerability Assessment can be found here. It assesses how climate change will impact 18 important species and 6 habitats within the Nooksack watershed. There are different sensitivity factors impacting the species. The information is presented in tables grouping vulnerable species under different RCP scenarios. Most species end up in the “Extremely vulnerable” category by 2050 and 2080. This is gloomy information, presented in a straightforward scientific manner.

These analysis of species vulnerability inspired me to start printmaking. I expanded upon the simple silhouette imagery used in the report and carved intricate animals from wood, then embossed those forms in thick paper, or printed them in ghostly shades of grey. I thought about fragility, transience and resilience in addition to vulnerability. I printed these animals by themselves, or under the strong and enduring outline of Mt. Baker. In the present, these animals characterize this place. Their bodies are linked to water bodies. They populate the Nooksack watershed and fill ecosystem niches. In the next 30 or 60 years, will they still be here? How will they adapt? What would this place be without them? These are the questions driving this work.

This ongoing experiment is one example of how I am creating data-inspired visuals, bridging art and science with the help of photographs, experiences and conversations with researchers and watershed stakeholders.