Visualizing the Range of Glaciers

This page served as a landing spot for sharing bits of my undergraduate environmental science honors thesis and related printmaking work. The North Cascades in Washington, the place I know as home, hold many glaciers that have complex ties to both ecological and human communities. Climate change is rewriting the state of these glaciers and the relationships that they can sustain. Although these connections are usually described by science, art is an expansive form of communicating a shifting landscape and its inhabitants. My project strove to explore a remarkable place in flux with various ways of knowing - scientific, personal, artistic, anecdotal. Enjoy these snippets, or download my entire thesis “Visualizing the Range of Glaciers: Science, Art and Narrative if you care to.

3: Pika Story

This “chapter” is written for the story of Vivid Glacier, a climate change glacier storytelling project organized by Mauri Pelto and executed by a variety of glaciologists, explorers and wonderers. As the rest of the chapters (written from other organisms points of view) emerge, I’ll share the links.

Also, many thanks to Emily Hyde for providing details from her experience counting pikas in the high deserts of Oregon!

EEE!

Hawk circles the sky, and I sound the alarm. The other pikas hear my shriek and we all dart beneath rocks. Summer sun bares down on the talus slope where I have lived my entire life. It’s the start of an August day, the hottest time of the year.

To avoid overheating I rest in the cool shadows during the day and forage diurnally. At this time of year, I don’t have to look far to find nourishing shrubs and flowers. The alpine meadows scattered across the slope are at the peak of summer abundance. Meltwater trickles down from Vivid glacier throughout the summer, and this cold water feeds the alpine vegetation. I gather mouthfuls of thistles, fireweed and alpine grasses. Once the stems are dry, I scuttle them to caches in the rock, deep piles of collected plants called haypiles. These will feed me throughout the winter.

EEE!

I shriek again, unsure if my fellow critters can hear or understand. This is not an alarm for the presence of owl or weasel or snake. It is something more dangerous than a predator—it is a temperature warning. Of any of the inhabitants of Vivid Glacier, we know the dangers of rising temperatures the best. We pikas die if exposed to temperatures of over 78°F for too long, temperatures that the lower rock fields now reach regularly in the summer. Generations ago, my family lived at the base of this slope- but even in the shelter of the rocks, the heat became deadly. So we have climbed to cooler, higher places. Pika by pika, we are forced to establish new homes higher on the mountain.

Temperature is forcing everyone to move up- the glacier, the forest, our predators and our forage. Sometimes we move at different paces, so each season contains unpredictable risks and possibilities. Forests take root in scree slopes that once were open snow and sun. Not long ago, the talus pile where I live was covered by the cold weight of Vivid Glacier. Currently, the rocks are dry four to six months of the year and crammed with a mosaic of alpine vegetation. It’s a good home for now, but I will nose my kids up the slope when they are born. Summer temperatures keep rising, and we must too. Between here and the remnant of Vivid Glacier and the mountain top, there isn’t that much room to move. What will happen when all of the alpine life is restricted to a mountaintop? Will it become a summit of sun-bleached bones?

This is looking to be a really hot summer. What can we do? I shriek for my neighbors, but my voice feels unusually small. I hear no chirps from downslope—and I worry that my lower relatives are dying. We are powerless in the heat.

Months pass, and the air cools. I’ve survived the heat of summer and stashed away many twigs and wildflowers. Now it begins to snow, light flurries at first, and then a huge storm bring deeper drifts. Within the rocks, I sit upon my favorite haypile and the slope grows very quiet.

Unlike bear, I don’t hibernate, and unlike many of the birds, I cannot migrate. I need a thick snow blanket to insulate my home. When there is enough snow, the ground temperature is stable at 32°F, and I can survive. Without snow, winter cold can be deadly. I know that we pikas often fail to reproduce when there is not an insulative snowpack. Additionally, our favorite plants suffer frost damage and we have less to eat when melt-off begins. The talus slope is better with baby pikas and abundant forage. In solitude, I hope for plenty of snowfall, especially if this winter is a cold one. Then I scurry out to excavate an air shaft and build a tunnel to access my haypiles. Even in winter, I don’t sit still for long.

Winter passes. Under the changing surface of the snow, I have survived another season. The only place I have ever known is the alpine, where blazing summer days contrast chilly nights and even more frigid winters. In the climate of the past, we pikas were well equipped. But every year is different now. Despite our adaptions for living in the extreme reaches of the alpine, this stochasticity challenges our biological strategies. Although this winter brought plenty of snow to envelope my territory, at the bottom of the slope where my ancestors once lived, things were different. There was little snow, exposing the plants and animals to bitter cold and low moisture. The alpine meadows withered, and shrubs took their place. It seems there is no way to survive down there now.

Another change this year is the quick arrival of spring. I get moving and foraging a month earlier than my ancestors did. Springtime seems as lush as ever, yet when I look for my favorite tufts of forget-me-nots, they’re no longer there. My favorite plants migrate upslope, or disappear, and new ones march into their rootwells. All I can do is change my diet.

Over the summer, less and less water trickles down from Vivid glacier, leaving the foliage thirsty and skimpy. I stockpile what I can, preparing for the uncertain months ahead. August feels much hotter, and I get close to overheating many days. The stress and solitude fatigue me.

Below, the talus slopes in the valley are ghostly quiet. No more EEE’s! rise on the mountain thermals. There are a few more pikas above me, at the upper limit of the rock below Vivid glacier. Our population struggles to find the spot where we can survive both summer and winter temperatures and find enough to eat. We are quickly running out of space. But the temperature marches constantly upward, past where we can go.

We will climb until the heat bleaches our bones.

Heed the warning of the Pika, sentinel of Vivid Glacier.

EEE!

More:

Ecological consequences of anomalies in atmospheric moisture and snowpack by Johnston et al. 2019

Pikas versus Trump, a vengeful game/app from the Center for Biological Diversity

2.1: Going to Stehekin

On Monday, June 15th, I left the Methow Valley and traveled to Stehekin, Washington. Here are early observations and reflections from the first stages of this trip.

The Great River: Columbia

Your power is turning our darkness to dawn

So roll on, Columbia, roll on

Woody Guthrie

On the banks of the Columbia River in North Central Washington, powerlines loom above ordered rows of apple trees and grape vines. Diagonal, vertical, a valley remade by thin lines. The river too becomes a line, a horizon. On the surface the Columbia looks motionless, her flow imperceptible. This languid river straddles the center of the valley, bisecting the tidy tiles of orchardry.

Hydropower and irrigation water are drawn from this great river, all throughout Washington State. This feeds the region’s growth and agriculture. With enough water, this is the ideal climate for apples.

I am looking into the valley where Chelan enters the Columbia. This is the land of the Chelan people. Downstream of here, the river is stoppered behind eight different dams: Bonneville, The Dalles, John Day, McNary, Priest Rapids, Wanapum, Rock Island, Rocky Reach. Upstream and damming the tributaries there are dozens more. Between dams, the river looks motionless. Yet inside the squat concrete dams, the water turns massive turbines and generates enormous amounts of electricity. One current transforms into another, powering lightbulbs, offices, microwaves and apple packing plants.

The scale of the Columbia River watershed and her hydropower generation is massive, nearly incomprehensible. The sheer size of one dam is overwhelming in person. Picturing the system that coordinates each concrete structure and kilowatt hour generates an abstract sense of scale. This view leaves many important small things unspoken. I’m interested in tracing the stories of the tributaries, the individuals and the water sources that feed into the larger story. I’m going to a small fraction of the Columbia River basin—one that is familiar, glacier fed, a bit easier to understand. To begin, I am getting on a boat.

The Long Lake: Tsi-laan

A settler named Ella Clark recorded this creation story from the Chelan nation: when Coyote came to the animal people along the Chelan River, he said to them, “I will send many salmon up your river if you will give me a nice young girl for my wife.” But the Chelan people refused. They thought it was not proper for a young girl to marry anyone as old as Coyote. So Coyote angrily blocked up the Canyon of Chelan River with huge rocks and thus made a waterfall. The water dammed up behind the rock and formed Lake Chelan. The salmon could never get past the waterfall. That is why there are no salmon in Lake Chelan to this day.”

I arrive on the Lake Chelan ferry dock for the 8:30 am boat to Stehekin. This ribbon of deep, cold water is 50 miles long and 1,485 feet deep at its lowest point – nearly 400 feet below sea level. The Lady Express motors northwest, beelining through the widest (2 miles) and narrowest (1/4 mile) sections of the lake. We quickly pass the agricultural communities and enter the reaches of undeveloped lakeshore. I scan the rocky cliffs for bighorn sheep but see none. Uplake, hiking trails and campgrounds dot the shoreline at long intervals.

Since the last ice age, when this lake is thought to have formed, this landscape has been changing. Lake Chelan was raised 21 feet in 1927 with the construction of the Lake Chelan Dam, a Chelan county hydropower project that provides Chelan and nearby communities with power. This area has some of the cheapest electricity rates in the country- residential rates are about 3¢ per kilowatt hour. For comparison, Seattle is around 11¢ per kWh, and New York City is 20¢ per kWh.

The level of the lake fluctuates seasonally as the Chelan County Public Utility District (PUD) makes room for spring runoff and allows water to pass through the turbines, spill into the tailrace, and enter the Columbia. During winter at the Stehekin end, low water levels expose mudflats that become snow covered. Spring warmth melts the snow and ice cradled in the mountains. The runoff raises the lake to its full green depth, making it sailboat-worthy by June. Nearly every summer afternoon a small crew headed by a man named Bob navigate a wooden sailboat called Ipsut around the head of the lake. Rough cliffs and forests loom high above. They tack back and forth, dodging stumps from days when the lake was lower, and tree trunks deposited by the Stehekin River.

The Wild River: Stehekin

Bob and Tammy live on the bank of the Stehekin River where it enters Lake Chelan. Just steps away from their living room, the river sings and flows. Three thousand cubic feet of June snowmelt glide by their house every second, refracting every possible shade of green.

This place becomes a passage for many things, and to live here is to be a listener. At night, rushing water rinses through dreams. During floods, stones knock against each other underwater. Every morning, hoots and chirps fill the air as all kinds of birds take wing above the river, using it as a passageway. Logs and sticks drift by and come to rest in the lake, building a web of wood on the delta. Wind settles down river and rustles the maple leaves. Sediment passes by. You can sense the geologic processes of erosion and deposition taking place, season after season. Bob and Tammy’s house is so close to the water you can close your eyes and hear precarity. In a geologic sense, this is an unlikely structure. So, to live here is to have a stake in the watershed, a willingness to live in the company of torrents, torpedoing logs and transient green water.

Bob and Tammy tell me their story of the October 2003 flood, when days of mountain snowfall and a rainstorm precipitated a 20,000 cfs flood that turned their home into an island and their yard into a kayak pool. As the lake filled up, it backed up towards their house, surrounding them with slow deep water. With three boys at home, they pulled propane tanks from the flood and tried to keep cars from floating away. The family watched as telephone pole height firs were wrenched out of the river and into the forest above their house.

One combination of weather events has the force to completely rearrange a dwelling place. Around Bob and Tammy’s, the 2003 flood stripped the beaches from the river banks and rearranged the rocks in the channel. Once, there was room for a parking lot between the river and their house. Now there is just a six-foot strip of grass and daisies. They know that the next flood could remake it all over again.

1: Carver Lake

With this post I am test driving this glacier-research-art blog and how I will document and process my work this summer. My summer research project will become a part of my environmental science honors thesis.

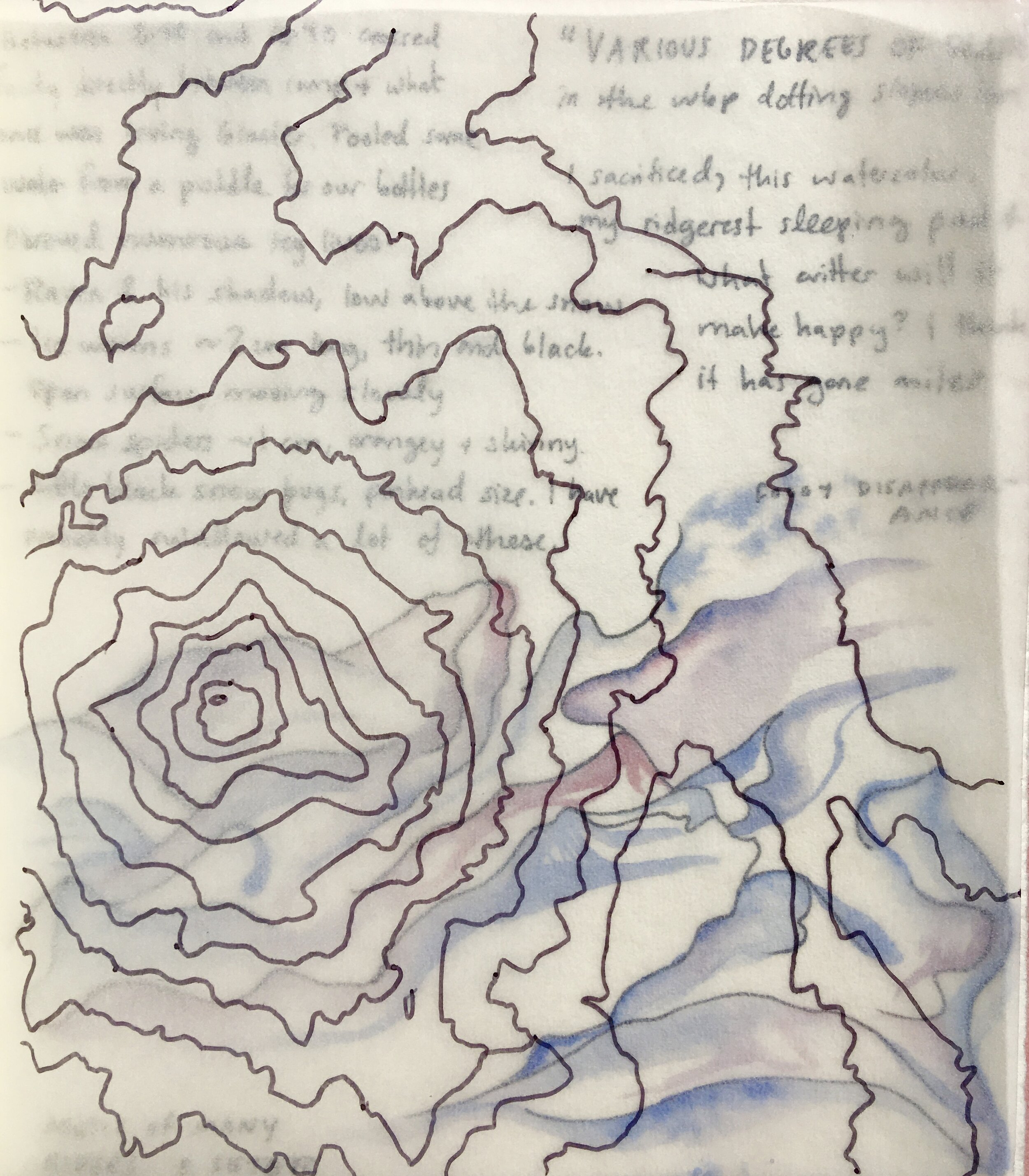

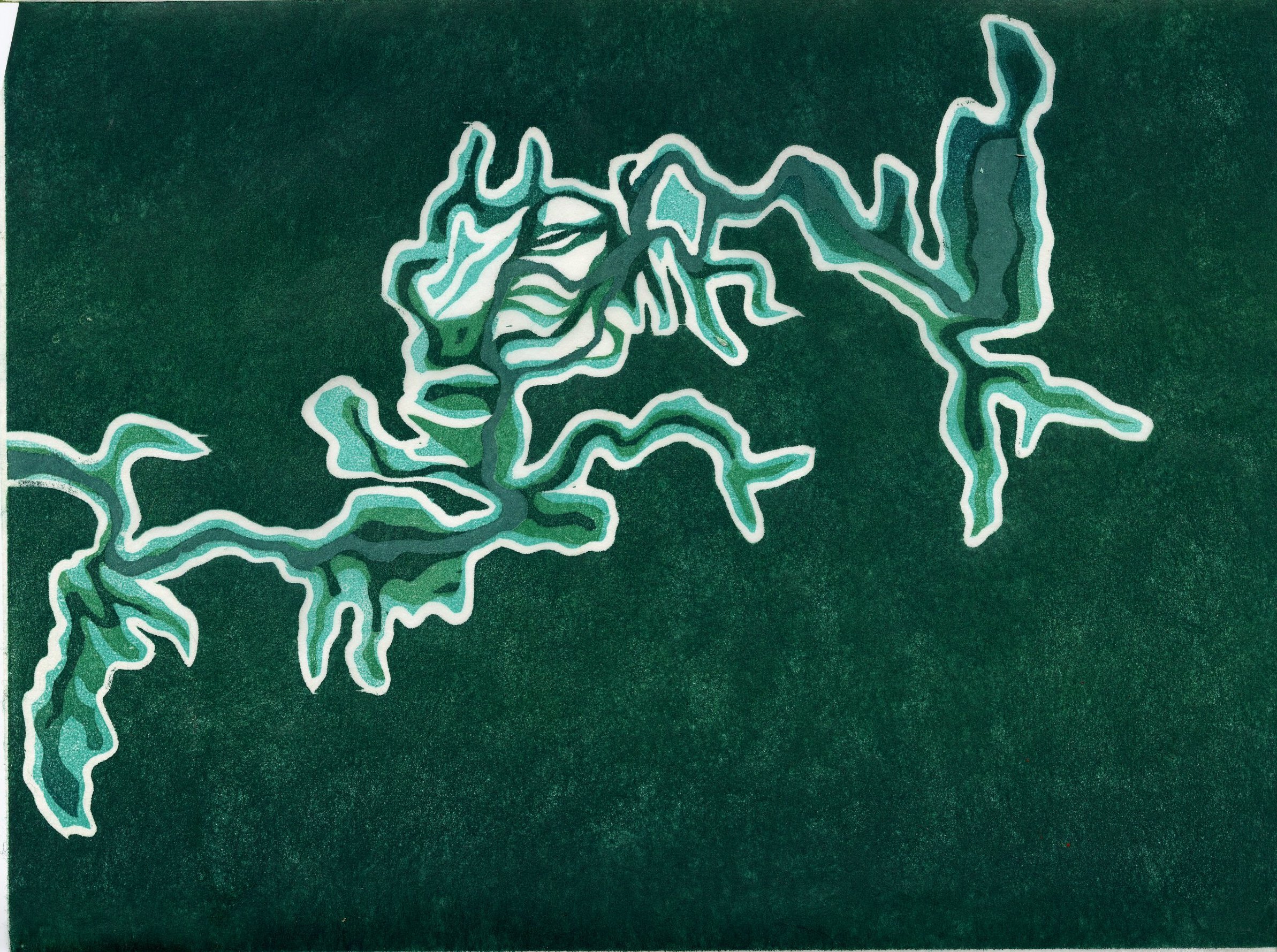

Collages of topography tracings, Carver Lake bathymetry, photos by Olivia Moehl, and watercolor journal pages.

Location: 44° 6'53.39"N. 121°44'44.84"W.

Local time: 5:41 am, 25th of May, 2020.

Cause of awakening: Sunlight seemingly rupturing the seams of the tent.

Company: My good friend Olivia, some instant mashed potatoes, and skis.

We are just waking up in a tent set on the East slope of South Sister, a volcano in the Three Sisters Wilderness of Central Oregon. Outside our zippers, the dawnsun blazes long blue shadows from the whitebark pine krummholz stands. Fog curls off the summits of Middle Sister and North Sister, resplendent in the early sky. After completing a pot of oatmeal and a watercolor painting, we pluck our drying skins from the arms of whitebark pine, smooth them onto our skis, and begin our glide north.

Our morning is spent exploring the wide, wonky saddle between South and Middle Sister, a landscape defined by hollows and surges. Everything but the crests of the moraines is filled with pure white snow. We weave between the snow-veiled Chambers Lakes and up to around 8,700 feet on Middle Sister. Then a cloud surrounds us. We have less than 100 feet of visibility. We descend back to the saddle and cross over to South Sister, where it is clearer. Winding upward through a new series of moraines and snowfields, we arrive at the base of South Sister’s eastern headwall.

A few hundred feet below us, we see a flat snowy plain, the signature of a wintry alpine lake. It is quietly snow covered, aside from a thin crescent of blue slush. This is Carver Lake, at 7,800 feet on the east face of South Sister. Surface area: 15.4 acres. Estimated volume: 740 acre feet. Carver pools deeply behind a loose, unvegetated moraine with distinctly pointy peaks. We could see these uprisings for miles although Carver Lake has remained invisible except from this Prouty glacier bowl.

Camp on the east face of South Sister. The peaks in the distance are Middle Sister on the left and North Sister on the right.

Moraines and lakes on the saddle between Middle and North Sister. On the right is one of the small Chambers Lakes, mostly covered in snow.

Viewing Carver Lake from above.

A snowfield slopes into the lake from the left.

A pyramidal moraine lies to the right of Carver’s outlet stream.

In 1987, researchers with the U.S. Geological Survey investigated the possibility for the glacial moraine holding back Carver Lake to fail. The precedent for researching this were three historical glacial moraine dams of the Sisters Range bursting in 1942, 1966 and 1970. Triggered by ice fall, some of those lakes emptied completely, and all caused large-magnitude floods affecting downstream communities. The authors write that due to the evidence of past breaches and floods,

“the frequency of breakouts of moraine-impounded lakes in the Three Sisters area can be considered to be greater than about one every 15 to 20 years (an annual probability of at least 5 to 6 percent) until moraine lakes in the area no longer exist).” (Laenen et al., 1987)

Few of these moraine lakes in Oregon are well studied, but researchers assume that the likelihood of any one lake failing is 1 percent a year. Of Carver lake they say,

“The topographic setting of the lake at the base of steep unstable masses of ice, snow, and rock, as well as the complete drainage of other moraine-dammed lakes in the area, clearly indicate that Carver Lake dam could fail catastrophically.”

If the lake were destabilized, there could be a catastrophic flood. This would theoretically be triggered by seismic activity and an avalanche or rockfall from the glacier and cliffs hanging above Carver Lake. Under an extreme scenario, ten-foot waves would swish across the lake and break the moraine dam, draining the entire volume of the lake within three minutes. The flood would swell to a magnitude ten times greater than a 1% probability meteorological flood. It would accumulate readily erodible glacial material in the steep Whychus creek channel, and double in volume over its first eight miles. At maximum discharge, the flow would be 180,000 cubic feet per second. Less than two hours after the avalanche, upon reaching the town of Sisters, Oregon, the flow would have debulked considerable amounts of sediment (up to 6 feet thick on the valley flats) but still could carry up to 9,800 cubic feet per second.

It wasn’t until we linked Prouty glacier to Carver Lake and then skied directly down from the lake to our camp that we realized how close to this looming hazard we were sleeping. To be sure, the calculations may have shifted since 1987: the gentle ice-free slope above Carver Lake on this May day did not seem to contain considerable avalanche risk. Many moraine dams fail within their first 20 years, and Carver appeared somewhere around 1930. However, it is pretty riveting to imagine the worst-case scenario. We would certainly be the first inundated or entombed casualties. Olivia and I live with strong links to mountainous terrain- she is a geologist; we both sketch, ski and study these places. By nature, our interests are bound to environmental losses and risks.

What is risk?

Is it camping beside a moraine that has a one percent chance of failing in a year?

Is it the act of exploring the unknown side of the mountain?

Is it letting ourselves love something that is melting?

I feel like I am riding the crest of a wave of environmental change. When I read, when I look underfoot, I see more loss. The more my awareness grows, the higher up I am pushed up on the wave; the more disasters, risks and injustices feed the wave. Historical patterns are ruptured by the wave. Assumptions dissolve. It’s almost impossible to find a balance point. The wave seems to tug at all lives, all places, all histories. Trying to build a sense of place during my lifetime is an exercise in constant change and adaptation. Meltwater loosens my grip on every solid thing.

The more I try to understand, the more I risk losing.

Still, I am pulled into the landscape of glaciers, mountains and rivers. This summer, I am diving in. I know that these things will change irreversibly within my lifetime. Glaciers will disappear. Gravity-hungry meltwater may the break moraines I have slept next to. I will share my summer with risk, with knowing what is changing and doing my best to share that. I don’t know what may become of my work, but I hope to at least raise awareness, which can be an attack on how we live our lives, combatting complacency towards climate change.

My relationship to the mountains is personal. It is through breathing mountain air, eddying into waterfalls and sweating buckets as I traverse folds of rock that I connect to mountains. I do not always think inside the rational forms of environmental science, but they are a very good tool. For observing and experimenting. Art is another tool. For remembering and imagining. I have dreams for this project, that I may use this trio of tools—science, art and alpinism-- to create something of meaning and importance. Now I will begin, writing, studying and creating.

Because,

We are losing glaciers.

We are losing a special, storied hue of blue.

Water gathers in deepening lakes, lakes that may burst and rush downstream.

We live downstream. We drink the glacier water.

The water within us was once ice.

Unlike the thicket-like peaks of the North Cascades, from the Sisters I look directly down to town. Water melts, collects in streams, feeds fields and waters people. In the crisp central Oregon air, these links are crystalized. 48 hours without seeing a stranger or a screen create space for reflecting and exploring deeply.

Yet this altitude also carries privilege. I have the time, resources and money to travel to remote places in the mountains. If glaciers melt, my life may lose meaning, but I will not lose my life. There are other people who bear much graver impacts of glaciers melting and eroding- people who likely do not have the resources to climb up to see the glaciers. The fields of science, conservation, glaciology and mountaineering have roots that are socially and culturally problematic, issues that still linger today.

As I enter this work, I commit to addressing the social dimensions of climate change in the best way I know how: using the tools of art and science to shape appreciation and concern for the changing environment, illuminating the people and places that struggle to make their voices heard.

More tidbits! A couple of the threads that link to everything else:

HISTORY

I’ve been fascinated with GLOFs (Glacial Lake Outburst Floods) since reading the book In the shadow of melting glaciers : climate change and Andean society by Mark Carey a few months ago.I had no idea that avalanche triggered GLOFs in the Cordillera Blanca took so many lives. In 1941, one GLOF devastated Huarez Peru, killing 4,000 people. The disasters also instigated many political and engineering projects, including a state glaciology unit charged with mitigating the hazards of GLOFs.In the Andes, as in the Cascades, climate change has melted glaciers, creating large glacial lakes below. Often the dams restricting the outflow of these lakes are merely loose deposits of rock the glacier once carried -- moraines. When an avalanche or rock slide (other events potentially increased in frequency/scope by anthropogenic climate change) hits the lake, the dams may burst. After reading about these catastrophes in the Andes, I was surprised to find myself so close to one.

WHITEBARK PINE

Whitebark pine are high-elevation guardians of snow. Up on South Sister, they protect long loaves of snow from the wind. These banks melt later than unsheltered snow, protracting mountain runoff. High elevation whitebark pine, or glacier wastage: two important and declining sources of late summer runoff. They’re incredibly tough trees, and it was a joy to camp among their wizened forms.